Section Formula

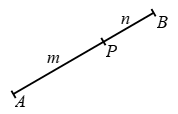

Let A and B be two points in the plane of the paper as shown in fig. and P be a point on the segment joining A and B such that AP : BP = m : n. Then, the point P divides segment AB internally in the ratio m : n.

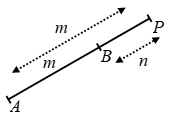

If P is a point on AB produced such that AP : BP = m : n, then point P is said to divide AB externally in the ratio m : n.

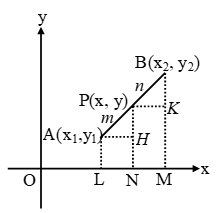

The coordinates of the point which divides the line segment joining the points (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) internally in the ratio m : n are given by

\( \left( x=\frac{m{{x}_{2}}+n{{x}_{1}}}{m+n},\ y=\frac{m{{y}_{2}}+n{{y}_{1}}}{m+n} \right) \)

The coordinates of P are \(\left( \frac{m{{x}_{2}}+n{{x}_{1}}}{m+n},\ \frac{m{{y}_{2}}+n{{y}_{1}}}{m+n} \right)\)

Note 1:

If P is the mid-point of AB, then it divides AB in the ratio 1 : 1, so its coordinates are

\(\left( \frac{1\ .\ {{x}_{1}}+1\,.\,{{x}_{2}}}{1+1},\ \frac{1\,.\,{{y}_{1}}+1\,.\,{{y}_{2}}}{1+1} \right)=\left( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}}{2},\ \frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}}{2} \right)\)

Note 2:

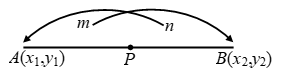

Fig. will help to remember the section formula.

Note 3:

The ratio m : n can also be written as \(\frac{m}{n}:1,\) or λ : 1, where λ = \(\frac{m}{n}:1.\)

So, the coordinates of point P dividing the line segment joining the points A(x1, y1) and B(x2, y2) are

\( \left( \frac{m{{x}_{2}}+n{{x}_{1}}}{m+n},\ \frac{m{{y}_{2}}+n{{y}_{1}}}{m+n} \right)=\left( \frac{\frac{m}{n}{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{1}}}{\frac{m}{n}+1},\ \frac{\frac{m}{n}{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{1}}}{\frac{m}{n}+1} \right) \)

\( \text{ }=\left( \frac{\lambda {{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{1}}}{\lambda +1},\ \frac{\lambda {{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{1}}}{\lambda +1} \right) \)

Read More: Distance between two points

Section Formula With Examples

Type I: On finding the section point when the section ratio is given

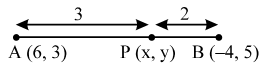

Example 1: Find the coordinates of the point which divides the line segment joining the points (6, 3) and (– 4, 5) in the ratio 3 : 2 internally.

Sol. Let P (x, y) be the required point. Then,

\( x=\frac{3\times (-4)+2\times 6}{3+2}\text{ and }y=\frac{3\times 5+2\times 3}{3+2} \)

\( \Rightarrow x=0\text{ and }y=\frac{21}{5} \)

So, the coordinates of P are (0, 21/5).

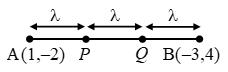

Example 2: Find the coordinates of points which trisect the line segment joining (1, –2) and (–3, 4).

Sol. Let A(1, –2) and B(–3, 4) be the given points.

Let the points of trisection be P and Q. Then,

AP = PQ = QB = λ (say).

∴ PB = PQ + QB = 2λ and AQ = AP + PQ = 2λ

⇒ AP : PB = λ : 2λ = 1 : 2 and

AQ : QB = 2λ : λ = 2 : 1

So, P divides AB internally in the ratio 1 : 2 while Q divides internally in the ratio 2 : 1. Thus, the coordinates of P and Q are

\( P\left( \frac{1\times (-3)+2\times 1}{1+2},\ \frac{1\times 4+2\times (-2)}{1+2} \right)=P\left( \frac{-1}{3},\ 0 \right) \)

\( Q\left( \frac{2\times (-3)+1\times 1}{2+1},\ \frac{2\times 4+1\times (-2)}{2+1} \right)=Q\left( \frac{-5}{3},\ 2 \right)\text{ respectively} \)

Hence, the two points of trisection are (–1/3, 0) and (–5/3, 2).

Type II: On Finding the section ratio or an end point of the segment when the section point is given

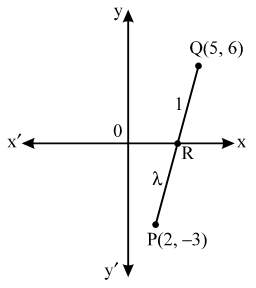

Example 3: In what ratio does the x-axis divide the line segment joining the points (2, –3) and (5, 6)? Also, find the coordinates of the point of intersection.

Sol. Let the required ratio be λ : 1. Then, the coordinates of the point of division are,

\( R\left( \frac{5\lambda +2}{\lambda +1},\ \frac{6\lambda -3}{\lambda +1} \right) \)

But, it is a point on x-axis on which y-coordinates of every point is zero.

\( \frac{6\lambda -3}{\lambda +1}=0 \)

\( \Rightarrow \lambda =\frac{1}{2} \)

Thus, the required ratio is 1/2 : 1 or 1 : 2.

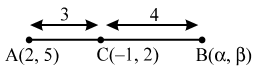

Example 4: If the point C (–1, 2) divides internally the line segment joining A (2, 5) and B in ratio 3 : 4, find the coordinates of B.

Sol. Let the coordinates of B be (α, β). It is given that AC : BC = 3 : 4. So, the coordinates of C are

\( \left( \frac{3\alpha +4\times 2}{3+4},\ \frac{3\beta +4\times 5}{3+4} \right)=\left( \frac{3\alpha +8}{7},\ \frac{3\beta +20}{7} \right) \)

But, the coordinates of C are (–1, 2)

\( \frac{3\alpha +8}{7}=-1\text{ and }\frac{3\beta +20}{7}=2 \)

⇒ α = – 5 and β = – 2

Thus, the coordinates of B are (–5, –2).

Example 5: Determine the ratio in which the line 3x + y – 9 = 0 divides the segment joining the points (1, 3) and (2, 7).

Sol. Suppose the line 3x + y – 9 = 0 divides the line segment joining A (1, 3) and B(2, 7) in the ratio k : 1 at point C. Then, the coordinates of C are

\( \left( \frac{2k+1}{k+1},\ \frac{7k+3}{k+1} \right) \)

But, C lies on 3x + y – 9 = 0. Therefore,

\( 3\left( \frac{2k+1}{k+1} \right)+\frac{7k+3}{k+1}-9=0 \)

⇒ 6k + 3 + 7k + 3 – 9k – 9 = 0

⇒ k = \(\frac { 3 }{ 4 }\)

So, the required ratio is 3 : 4 internally.

Type III : On determination of the type of a given quadrilateral

Example 6: Prove that the points (–2, –1), (1, 0), (4, 3) and (1, 2) are the vertices of a parallelogram. Is it a rectangle ?

Sol. Let the given point be A, B, C and D respectively. Then,

Coordinates of the mid-point of AC are

\( \left( \frac{-2+4}{2},\ \frac{-1+3}{2} \right)=(1,\text{ }1) \)

Coordinates of the mid-point of BD are

\( \left( \frac{1+1}{2},\ \frac{0+2}{2} \right)=(1,\text{ }1) \)

Thus, AC and BD have the same mid-point. Hence, ABCD is a parallelogram.

Now, we shall see whether ABCD is a rectangle or not.

We have,

\( AC=\sqrt{{{(4-(-2))}^{2}}+{{(3-(-1))}^{2}}}=2 \)

\( and,~~~~~BD\text{ }=\sqrt{{{(1-1)}^{2}}+{{(0-2)}^{2}}}=2 \)

Clearly, AC ≠ BD. So, ABCD is not a rectangle.

Example 7: Prove that (4, – 1), (6, 0), (7, 2) and (5, 1) are the vertices of a rhombus. Is it a square?

Sol. Let the given points be A, B, C and D respectively. Then,

Coordinates of the mid-point of AC are

\( \left( \frac{4+7}{2},\ \frac{-1+2}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{11}{2},\ \frac{1}{2} \right) \)

Coordinates of the mid-point of BD are

\( \left( \frac{6+5}{2},\ \frac{0+1}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{11}{2},\ \frac{1}{2} \right) \)

Thus, AC and BD have the same mid-point.

Hence, ABCD is a parallelogram.

\( Now,\text{ }AB=\sqrt{{{(6-4)}^{2}}+{{(0+1)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{5} \)

\( BC=\sqrt{{{(7-6)}^{2}}+{{(2-0)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{5} \)

∴ AB = BC

So, ABCD is a parallelogram whose adjacent sides are equal.

Hence, ABCD is a rhombus.

We have,

\( AC=\sqrt{{{(7-4)}^{2}}+{{(2+1)}^{2}}}=3\sqrt{2}\text{ and} \)

\( BD=\sqrt{{{(6-5)}^{2}}+{{(0-1)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{2} \)

Clearly, AC ≠ BD.

So, ABCD is not a square.

Type IV: On finding the unknown vertex from given points

Example 8: The three vertices of a parallelogram taken in order are (–1, 0), (3, 1) and (2, 2) respectively. Find the coordinates of the fourth vertex.

Sol. Let A(–1, 0), B(3, 1), C(2, 2) and D(x, y) be the vertices of a parallelogram ABCD taken in order. Since, the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

∴ Coordiantes of the mid-point of AC = Coordinates of the mid-point of BD

\( \Rightarrow \left( \frac{-1+2}{2},\ \frac{0+2}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{3+x}{2},\ \frac{1+y}{2} \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \left( \frac{1}{2},\ 1 \right)=\left( \frac{3+x}{2},\ \frac{y+1}{2} \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \frac{3+x}{2}=\frac{1}{2}\text{ and }\frac{y+1}{2}=1 \)

⇒ x = – 2 and y = 1

Hence, the fourth vertex of the parallelogram is (–2, 1).

Example 9: If the points A (6, 1), B (8, 2), C(9, 4) and D(p, 3) are vertices of a parallelogram, taken in order, find the value of p.

Sol. We know that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. So, coordinates of the mid-point of diagonal AC are same as the coordinates of the mid-point of diagonal BD.

\( \left( \frac{6+9}{2},\ \frac{1+4}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{8+p}{2},\ \frac{2+3}{2} \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \left( \frac{15}{2},\ \frac{5}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{8+p}{2},\ \frac{5}{2} \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \frac{15}{2}=\frac{8+p}{2} \)

⇒ 15 = 8 + p

⇒ p = 7

Example 10: If A(–2, –1), B(a, 0), C(4, b) and D(1, 2) are the vertices of a parallelogram, find the values of a and b.

Sol. We know that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. Therefore, the coordinates of the mid-point of AC are same as the coordinates of the mid-point of BD i.e.,

\( \left( \frac{-2+4}{2},\ \frac{-1+b}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{a+1}{2},\ \frac{0+2}{2} \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \left( 1,\ \frac{b-1}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{a+1}{2},\ 1 \right) \)

\( \Rightarrow \frac{a+1}{2}=1\text{ and }\frac{b-1}{2}=1 \)

⇒ a + 1 = 2 and b – 1 = 2

⇒ a = 1 and b = 3

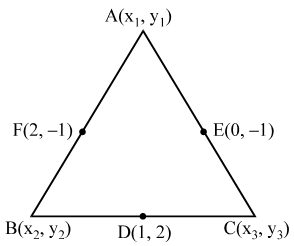

Example 11: If the coordinates of the mid-points of the sides of a triangle are (1, 2) (0, –1) and (2, 1). Find the coordinates of its vertices.

Sol. Let A(x1, y1), B(x2, y2) and C(x3, y3) be the vertices of ∆ABC. Let D (1, 2), E (0, –1), and F(2, –1) be the mid-points of sides BC, CA and AB respectively. Since D is the mid-point of BC.

\( \frac{{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{3}}}{2}=1\text{ and }\frac{{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{3}}}{2}=2 \)

⇒ x2 + x3 = 2 and y2 + y3 = 4 …. (1)

Similarly, E and F are the mid-point of CA and AB respectively.

\( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{3}}}{2}=0\text{ and }\frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{3}}}{2}=-1 \)

⇒ x1 + x3 = 0 and y1 + y3 = – 2 …. (2)

\( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}}{2}=2\text{ and }\frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}}{2}=-1 \)

⇒ x1 + x2 = 4 and y1 + y2 = –2 …. (3)

From (1), (2) and (3), we get

(x2 + x3) + (x1 + x3) + (x1 + x2) = 2 + 0 + 4 and,

(y2 + y3) + (y1 + y3) + (y1 + y2) = 4 –2 – 2

⇒ 2(x1 + x2 + x3) = 6 and 2(y1 + y2 + y3) = 0 …. (4)

⇒ x1 + x2 + x3 = 3

and y1 + y2 + y3 = 0

From (1) and (4), we get

x1 + 2 = 3 and y1 + 4 = 0

⇒ x1 = 1 and y1 = – 4

So, the coordinates of A are (1, – 4)

From (2) and (4), we get

x2 + 0 = 3 and y2 – 2 = 0

⇒ x2 = 3 and y2 = 2

So, coordinates of B are (3, 2)

From (3) and (4), we get

x3 + 4 = 3 and y3 – 2 = 0

⇒ x3 = – 1 and y3 = 2

So, coordinates of C are (–1, 2)

Hence, the vertices of the triangle ABC are

A(1, – 4), B(3, 2) and C(–1, 2).

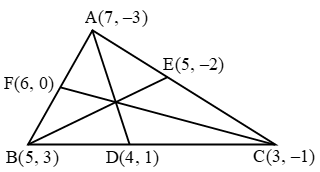

Example 12: Find the lengths of the medians of a ∆ABC whose vertices are A(7, –3), B(5,3) and C(3,–1).

Sol. Let D, E, F be the mid-points of the sides BC, CA and AB respectively. Then, the coordinates of D, E and F are

\( D\left( \frac{5+3}{2},\ \frac{3-1}{2} \right)=D(4,\text{ 1}), \)

\( E\left( \frac{3+7}{2},\ \frac{-1-3}{2} \right)=E\left( 5,2 \right) \)

\( and,\text{ }\left( \frac{7+5}{2},\ \frac{-3+3}{2} \right)=\text{ }F\left( 6,\text{ }0 \right) \)

\( AD=\sqrt{{{(7-4)}^{2}}+{{(-3-1)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{9+16}=5\text{ }units \)

\( BE=\sqrt{{{(5-5)}^{2}}+{{(-2-3)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{0+25}=5\text{ }units \)

\( and,~~~~~CF=\sqrt{{{(6-3)}^{2}}+{{(0+1)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{9+1}=\sqrt{10}\text{ }units \)

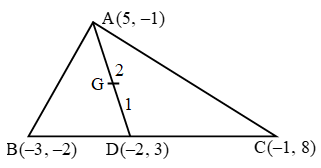

Example 13: If A (5, –1), B(–3, –2) and C(–1, 8) are the vertices of triangle ABC, find the length of median through A and the coordinates of the centroid.

Sol. Let AD be the median through the vertex A of ∆ABC. Then, D is the mid-point of BC. So, the coordinates of

\( \left( \frac{-3-1}{2},\ \frac{-2+8}{2} \right)i.e.,\left( 2,\text{ }3 \right). \)

\( AD=\sqrt{{{(5+2)}^{2}}+{{(-1-3)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{49+16}=\sqrt{65}~\text{ }units \)

Let G be the centroid of ∆ABC. Then, G lies on median AD and divides it in the ratio 2 : 1. So, coordinates of G are

\( \left( \frac{2\times (-2)+1\times 5}{2+1},\ \frac{2\times 3+1\times (-1)}{2+1} \right) \)

\( =\left( \frac{-4+5}{3},\ \frac{6-1}{3} \right)=\left( \frac{1}{3},\ \frac{5}{3} \right) \)

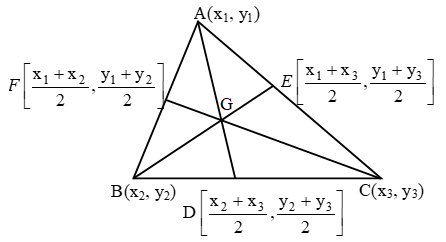

Application Of Section Formula

The coordinates of the centroid of the triangle whose vertices are (x1, y1), (x2, y2) and (x3, y3) are

\(\left( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{3}}}{3},\ \frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{3}}}{3} \right)\)

Example 14: Find the coordinates of the centroid of a triangle whose vertices are (–1, 0), (5, –2) and (8, 2).

Sol. We know that the coordinates of the centroid of a triangle whose angular points are (x1, y1), (x2, y2) and (x3, y3) are

\(\left( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{3}}}{3},\ \frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{3}}}{3} \right)\)

So, the coordiantes of the centroid of a triangle whose vertices are (–1, 0), (5, –2) and (8, 2) are

\(\left( \frac{-1+5+8}{3},\,\frac{0-2+2}{3} \right)or,\left( 4,\text{ }0 \right)\)

Example 15: If the coordinates of the mid points of the sides of a triangle are (1, 1), (2, – 3) and (3, 4) Find its centroid.

Sol. Let P (1, 1), Q(2, –3), R(3, 4) be the mid-points of sides AB, BC and CA respectively of triangle ABC. Let A(x1, y1), B(x2, y2) and C(x3, y3) be the vertices of triangle ABC. Then, P is the mid-point of BC

\( \Rightarrow \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}}{2}=1,\text{ }\frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}}{2}=1 \)

⇒ x1 + x2 = 2 and y1 + y2 = 2 …(1)

Q is the mid-point of BC

\( \Rightarrow \frac{{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{3}}}{2}=2,\text{ }\frac{{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{3}}}{2}=-3 \)

⇒ x2 + x3 = 4 and y2 + y3 = – 6 …(2)

R is the mid-point of AC

\( \Rightarrow \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{3}}}{2}=3,\text{ }\frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{3}}}{2}=4 \)

⇒ x1 + x3 = 6 and y11 + y3 = 8 …(3)

From (1), (2) and (3), we get

x1 + x2 + x2 + x3 + x1 + x3 = 2 + 4 + 6

and, y1 + y2 + y2 + y3 + y1 + y3 = 2 – 6 + 8

x1 + x2 + x3 = 6 and y1 + y2 + y3 = 2 …(4)

The coordinates of the centroid of ∆ABC are

\( \left( \frac{{{x}_{1}}+{{x}_{2}}+{{x}_{3}}}{3},\ \frac{{{y}_{1}}+{{y}_{2}}+{{y}_{3}}}{3} \right)=\left( \frac{6}{3},\ \frac{2}{3} \right) \)

\( =\left( 2,\ \frac{2}{3} \right)\text{ }\left[ Using\text{ }\left( 4 \right) \right] \)

Example 16: Two vertices of a triangle are (3, –5) and (–7, 4). If its centroid is (2, –1). Find the third vertex.

Sol. Let the coordinates of the third vertex be (x, y). Then,

\(\frac{x+3-7}{3}=2\text{ and }\frac{y-5+4}{3}=-1\)

⇒ x – 4 = 6 and y – 1 = – 3

⇒ x = 10 and y = – 2

Thus, the coordinates of the third vertex are (10, –2).

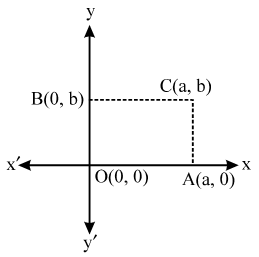

Example 17: Prove that the diagonals of a rectangle bisect each other and are equal.

Sol. Let OACB be a rectangle such that OA is along x-axis and OB is along y-axis. Let OA = a and OB = b.

Then, the coordinates of A and B are (a, 0) and (0, b) respectively.

Since, OACB is a rectangle. Therefore,

AC = Ob ⇒ AC = b

Thus, we have

OA = a and AC = b

So, the coordiantes of C are (a, b).

The coordinates of the mid-point of OC are

\( \left( \frac{a+0}{2},\ \frac{b+0}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{a}{2},\ \frac{b}{2} \right) \)

Also, the coordinates of the mid-points of AB are

\( \left( \frac{a+0}{2},\ \frac{0+b}{2} \right)=\left( \frac{a}{2},\ \frac{b}{2} \right) \)

Clearly, coordinates of the mid-point of OC and AB are same.

Hence, OC and AB bisect each other.

\( Also,~OC\text{ }=\sqrt{{{a}^{2}}+{{b}^{2}}}\text{ and} \)

\( AB\text{ }=\sqrt{{{(a-0)}^{2}}+{{(0-b)}^{2}}}=\sqrt{{{a}^{2}}+{{b}^{2}}} \)

∴ OC = AB