How Do You Prove Triangles Are Congruent

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GmS-p1S_t5E

Congruent Figures

Two figures/objects are said to be congruent if they are exactly of the same shape and size. The relationship between two congruent figures is called congruence. We use the symbol ≅ for ‘congruent to’.

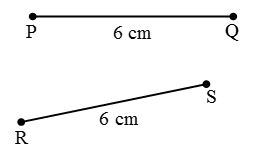

- Congruence among line segments: Two line segments are congruent if they have the same length.

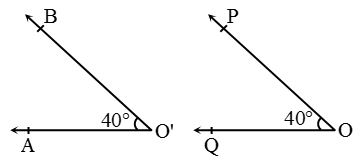

Thus, line segment PQ ≅ line segment RS as PQ = RS = 6 cm. - Congruence of Angles: Two angles are congruent if they have the same measure.

Thus, ∠AO’B ≅ ∠QOP,

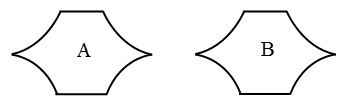

as m ∠AO’B = m ∠QOP = 40°. - Congruence of plane figures: Two plane figures A and B are congruent as they superpose each other. We can write it as figure A ≅ figure B.

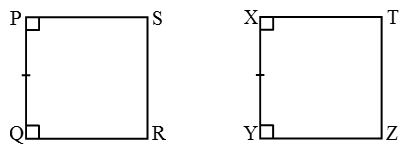

- Congruence of squares: Two squares are congruent if they have same side length.

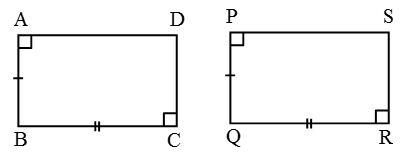

Square PQRS ≅ Square XYZT as PQ = XY. - Congruence of rectangles: Two rectangles are said to be congruent if they have the same length and breadth.

Rectangle ABCD ≅ Rectangle PQRS as

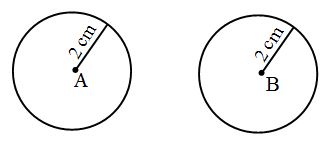

AB = PQ and BC = QR. - Congruence of circles: Two circles are congruent if they have the same radius.

Circle A ≅ Circle B, as radius of A = radius of B = 2 cm.

Congruence of Triangles

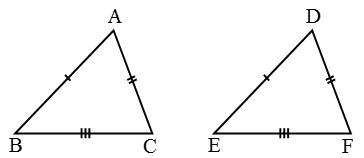

Two triangles are congruent if they are copies of each other, and when superposed they cover each other exactly.

∆ABC and ∆DEF have the same size and shape. They are congruent. So we would express this as ∆ABC ∆DEF. This means that, when we place ∆DEF on ∆ABC, D falls on A, E falls on B and F falls on C, also \(\overline { DE }\) falls along \(\overline { AB } ,\overline { EF }\) falls along \(\overline { BC }\) and \(\overline { DF }\) falls along \(\overline { AC }\).

∆ABC and ∆DEF have the same size and shape. They are congruent. So we would express this as ∆ABC ∆DEF. This means that, when we place ∆DEF on ∆ABC, D falls on A, E falls on B and F falls on C, also \(\overline { DE }\) falls along \(\overline { AB } ,\overline { EF }\) falls along \(\overline { BC }\) and \(\overline { DF }\) falls along \(\overline { AC }\).

- Corresponding angles are: ∠A and ∠D, ∠B and ∠E, ∠C and ∠F.

- Corresponding vertices are: A and D, B and E, C and F.

- Corresponding sides are: \(\overline { AB }\) and \(\overline { DE } ,\overline { BC }\) and \(\overline { EF } ,\overline { AC }\) and \(\overline { DF }\).

Hence, three sides and three angles are the six matching parts for the congruence of triangles.

Examples:

1. Write the correspondence between the vertices, sides and angles of the triangles XYZ and MLN, if ∆XYZ ≅ ∆MLN.

Solution:

By the order of letters, we find that

X ↔ M, Y ↔ L and Z ↔ N

∴ XY = ML, YZ = LN, XZ = MN

Also ∠X = ∠M, ∠Y = ∠L and ∠Z = ∠N.

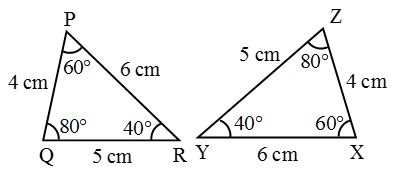

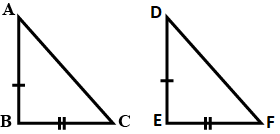

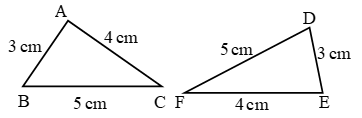

2. In following pairs of triangles, find the correspondence between the triangles so that they are congruent.

In ∆PQR: PQ = 4 cm, QR = 5 cm, PR = 6 cm, ∠P = 60°, ∠Q = 80°, ∠R = 40°.

In ∆XYZ: XY = 6 cm, ZY = 5 cm, XZ = 4 cm, ∠X = 60°, ∠Y = 40°, ∠Z = 80°.

Solution:

Let us draw the triangles and write the measures of their corresponding parts along with them.

From the above figures, we note that

PQ = XZ, QR = YZ, PR = XY

and ∠P = ∠X, ∠Q = ∠Z, ∠R = ∠Y

∴ P ↔ X, Q ↔ Z and R ↔ Y

Hence, ∆PQR ≅ ∆XZY

Read More:

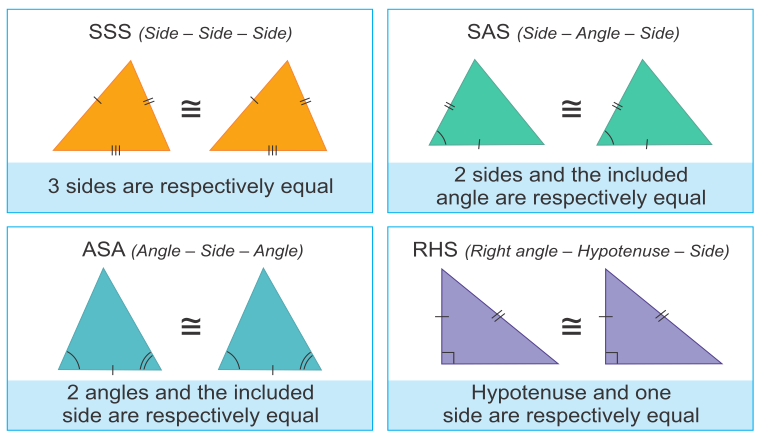

- Criteria For Congruent Triangles

- RS Aggarwal Class 7 Maths Solutions Congruence

- RS Aggarwal Class 9 Solutions Congruence of Triangles and Inequalities in a Triangle

Some more results based on congruent triangles:

- If two sides of a triangle are unequal, then the longer side has the greater angle opposite to it.

- In a triangle, the greater angle has the longer side opposite to it.

- Of all the line segments that can be drawn to a given line, from a point not lying on it, the perpendicular line segment is the shortest.

- The sum of any two sides of a triangle is greater than its third side.

- The difference between any two sides of a triangle is less than its third side.

- Exterior angle is greater than one opposite interior angle.

Congruent Triangles Example Problems With Solutions

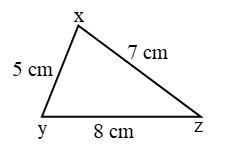

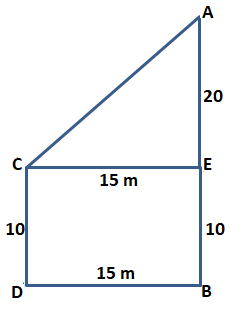

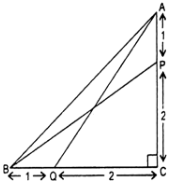

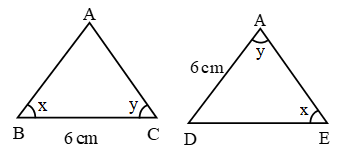

Example 1: Find the relation between angles in figure.

Solution: ∵ yz > xz > xy

⇒∠x > ∠y > ∠z.

(∵ Angle opposite to longer side is greater)

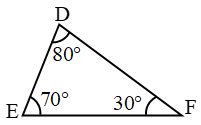

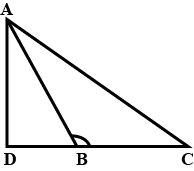

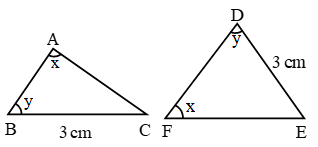

Example 2: Find the relation between the sides of triangle in figure.

Solution: ∵ ∠D > ∠E > ∠F

∴EF > DF > DE

{∵ side opposite to greater angle is longer}

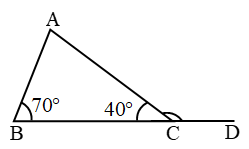

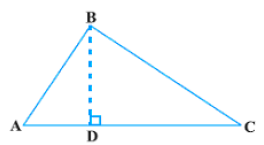

Example 3: Find ∠ACD then what is the relation between (i) ∠ACD, ∠ABC (ii) ∠ACD & ∠A

Solution: ∠ACD + 40° = 180° (linear pair)

∠ACD = 140°

also ∠A + ∠B = ∠ACD

(exterior angle = sum of opp. interior angles)

⇒ ∠A + 70° = 140° ⇒ ∠A = 140° – 70°

⇒ ∠A = 70°

Now ∠ACD > ∠B

∠ACD > ∠A

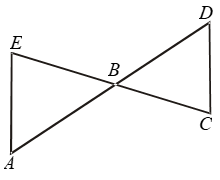

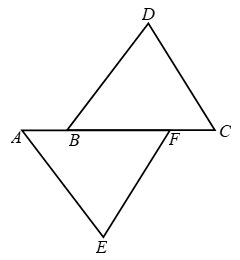

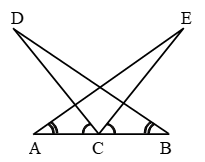

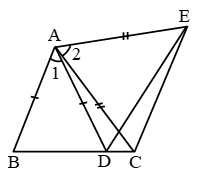

Example 4: In Fig. ∠E > ∠A and ∠C > ∠D. Prove that AD > EC.

Solution: In ∆ABE, it is given that

∠E > ∠A

⇒ AB > BE …. (i)

In ∆BCD, it is given that

∠C > ∠D

⇒ BD > BC …. (ii)

Adding (i) and (ii), we get

AB + BD > BE + BC ⇒AD > EC

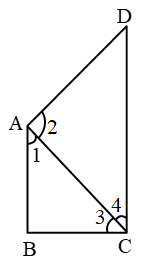

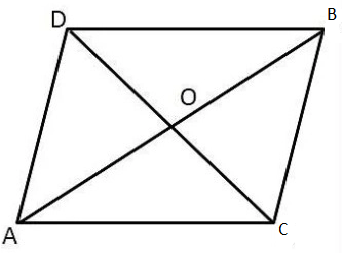

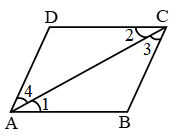

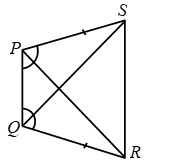

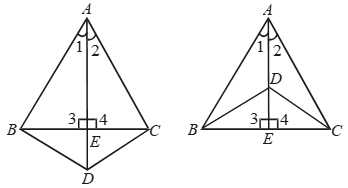

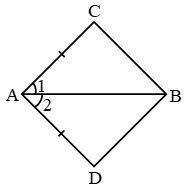

Example 5: AB and CD are respectively the smallest and longest sides of a quadrilateral ABCD (see figure). Show that ∠A > ∠C.

Solution: Draw diagonal AC.

In ∆ABC, AB < BC {∵ AB is smallest}

⇒ ∠3 < ∠1 ……(1)

{angle opp. to longer side is larger}

Also in ∆ADC

AD < CD ∵ CD is longest

⇒ ∠4 < ∠2 …..(2)

adding equation (1) & (2)

∠3 + ∠4 < ∠1 + ∠2

∠C < ∠A

or ∠A > ∠C Proved.

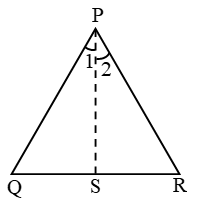

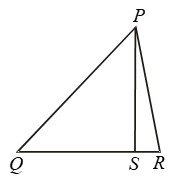

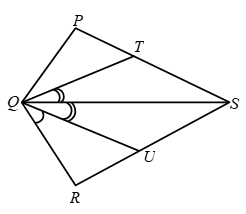

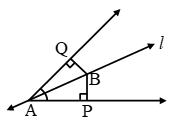

Example 6: In given figure, PR > PQ and PS bisects ∠QPR. Prove that ∠PSR > ∠PSQ.

Solution: In ∆PQR, PR > PQ

⇒ ∠Q > ∠R ……(1)

{angle opposite to longer side is greater}

and ∠1 = ∠2 (∵ PS is ∠bisector) ….(2)

Now for ∆PQS, ∠PSR = ∠Q + ∠1 ….(3)

{exterior angle = sum of opposite interior angle}

& for ∆PSR, ∠PSQ = ∠R + ∠2 ….(4)

By equation (1), (2), (3), (4), ∠PSR > ∠PSQ

Proved.

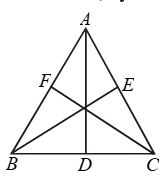

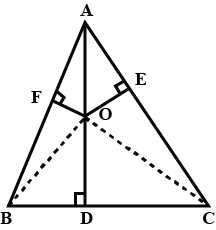

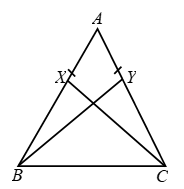

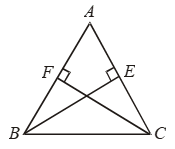

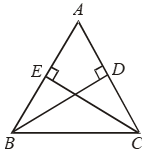

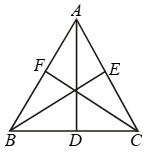

Example 7: AD, BE and CF, the altitudes of ∆ABC are equal. Prove that ∆ABC is an equilateral triangle.

Solution:

In right triangles BCE and BFC, we have

Hyp. BC = Hyp. BC

BE = CF [Given]

So, by RHS criterion of congruence,

ΔBCE ≅ ΔBFC.

⇒ ∠B = ∠C

⇒ AC = AB …. (i)

[∵ Sides opposite to equal angles are equal]

Similarly, ΔABD ≅ ΔABE

⇒ ∠B = ∠A

[∵ Corresponding parts of congruent triangles are equal]

⇒ AC = BC …. (ii)

[∵ Sides opposite to equal angles are equal]

From (i) and (ii), we get

AB = BC = AC

Hence, ΔABC is an equilateral triangle.

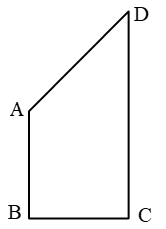

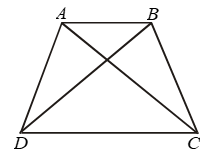

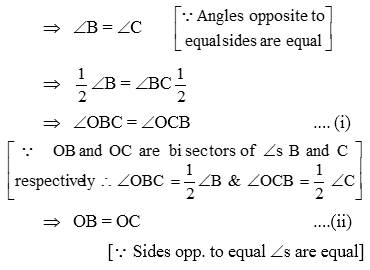

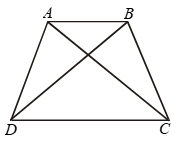

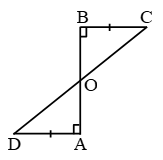

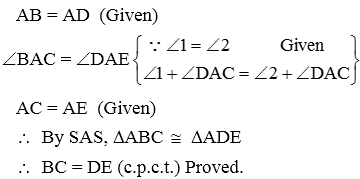

Example 8: In Fig. AD = BC and BD = CA.

Prove that ∠ADB = ∠BCA and ∠DAB = ∠CBA.

Solution:

In triangles ABD and ABC, we have

AD = BC [Given]

BD = CA [Given]

and AB = AB [Common]

So, by SSS congruence criterion, we have

ΔABD ≅ ΔCBA ⇒ ∠DAB = ∠ABC

[∵ corresponding parts of congruent triangles are equal]

⇒ ∠DAB = ∠CBA

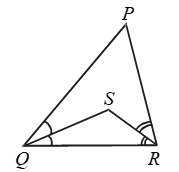

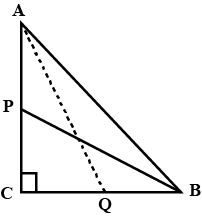

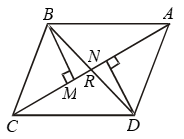

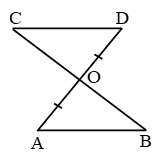

Example 9: In Fig. PQ > PR. QS and RS are the bisectors of ∠Q and ∠R respectively. Prove that SQ > SR.

Solution:

In ΔPQR, we have

PQ > PR [Given]

⇒ ∠PRQ > ∠PQR

[∵ Angle opp. to larger side of a triangle is greater]

⇒ \(\frac { 1 }{ 2 } \)∠PRQ > \(\frac { 1 }{ 2 } \)∠PQR

[∵ RS and QS are bisectors of ∠PRQ and ∠PQR respectively]

⇒ ∠SRQ > ∠SQR

⇒ SQ > SR

[∵ Side opp. to greater angle is larger]

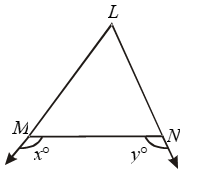

Example 10: In Fig.

if x > y, show that ∠M > ∠N.

Solution:

We have,

∠LMN + xº = 180º …. (i)

[Angles of a linear pair]

⇒ ∠LNM + yº = 180º …. (ii)

[Angles of a linear pair]

∴ ∠LMN + xº = ∠LNM + yº

But x > y. Therefore,

∠LMN < ∠LNM

⇒ ∠LNM > ∠LMN

⇒ LM > LN

[∵ Side opp. to greater angle is larger]

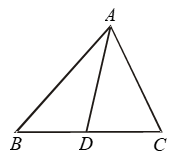

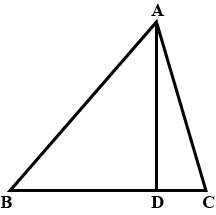

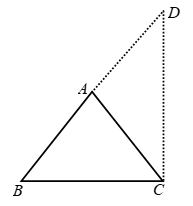

Example 11: In Fig. AB > AC. Show that AB > AD.

Solution:

In ΔABC, we have

AB > AC [Given]

⇒ ∠ACB > ∠ABC …. (i)

[∵ Angle opp. to larger side is greater]

Now, in ΔACD, CD is produced to B, forming an ext ∠ADB.

⇒ ∠ADB > ∠ACD

[∵ Exterior angle of Δ is greater than each of interior opp. angle]

⇒ ∠ADB > ∠ACB … (ii)

[∴ ∠ACD = ∠ACB]

From (i) and (ii), we get

∠ADB > ∠ABC

⇒ ∠ADB > ∠ABD [∵ ∠ABC = ∠ABD]

⇒ AB > AD

[∵ Side opp. to greater angle is larger]

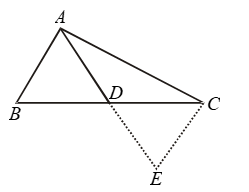

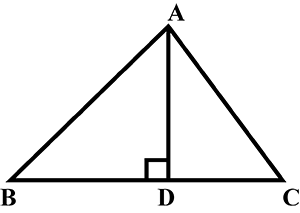

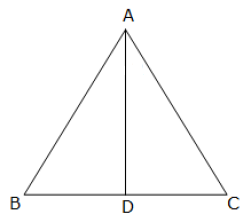

Example 12: Prove that any two sides of a triangle are together greater than twice the median drawn to the third side.

Solution:

To prove: AB + AC > 2 AD

Construction: Produce AD to E such that AD = DE. Join EC.

Proof: In Δ’s ADB and EDC, we have

AD = DE [By construction]

BD = DC [∵ D is the mid point of BC]

and, ∠ADB = ∠EDC [Vertically opp. angles]

So, by SAS criterion of congruence

⇒ ΔADB ≅ ΔEDC

⇒ AB = EC [∵ corresponding parts of congruent triangles are equal]

Now in ΔAEC, we have

AC + EC > AE [∵ Sum of any two sides of a Δ is greater than the third]

⇒ AC + AB > 2 AD

[∵ AD =DE ∴ AE = AD + DE = 2AD and EC = AB]

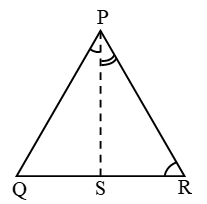

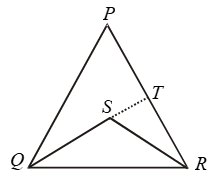

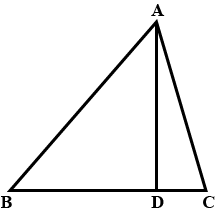

Example 13: In Fig. PQR is a triangle and S is any point in its interior, show that SQ + SR < PQ + PR.

Solution:

Given: S is any point in the interior of ΔPQR.

To Prove: SQ + SR < PQ + PR

Construction: Produce QS to meet PR in T.

Proof: In PQT, we have

PQ + PT > QT [∵ Sum of the two sides of a Δ is greater than the third side]

⇒ PQ + PT > QS + ST …. (i)

[∵ QT = QS + ST]

In ΔRST, we have

ST + TR > SR …. (ii)

Adding (i) and (ii), we get

PQ + PT + ST + TR > SQ + ST + SR

⇒ PQ + (PT + TR) > SQ + SR

⇒ PQ + PR > SQ + SR ⇒ SQ + SR < PQ + PR.

Example 14: In ∆PQR S is any point on the side QR. Show that PQ + QR + RP > 2 PS.

Solution:

In ΔPQS, we have

PQ + QS > PS … (i)

[∵ Sum of the two sides of a Δ is greater than the third side]

Similarly, in ΔPRS, we have

RP + RS > PS …. (ii)

Adding (i) and (ii), we get

(PQ + QS) + (RP + RS) > PS + PS

⇒ PQ + (QS + RS) + RP > 2 PS

⇒ PQ + QR + RP > 2 PS

[∵ QS + RS = QR]

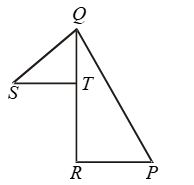

Example 15: In Fig. T is a point on side QR of ∆PQR and S is a point such that RT = ST.

Prove that PQ + PR > QS.

Solution:

In ΔPQR, we have

PQ + PR > QR

⇒ PQ + PR > QT + RT [∵ QR = QT + RT]

⇒ PQ + PR > QT + ST …. (i)

[∵ RT = ST (Given)]

In ΔQST, we have

QT + ST > QS …. (ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

PQ + PR > QS.

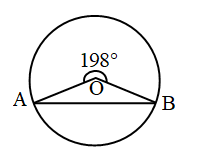

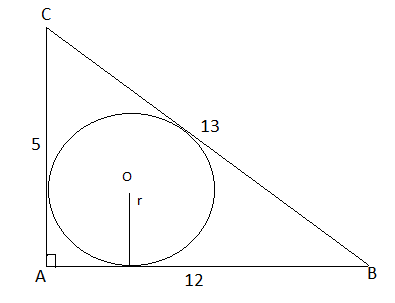

Example 16: Find ∠OBA in given figure

Solution:

∵ ∠AOB + 198° = 360°

∠AOB = 360° – 198° = 162°

and OA = OB = radius of circle

∠A = ∠B = x (let)

∴ x + x + 162° = 180° (a.s.p.)

2x + 18°

x = 9°

∴ ∠OBA = 9°.

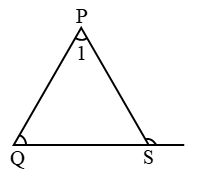

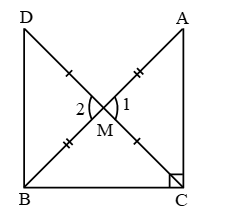

In figure, PQ ≠ QR ≠ PR, so ΔPQR is a scalene triangle.

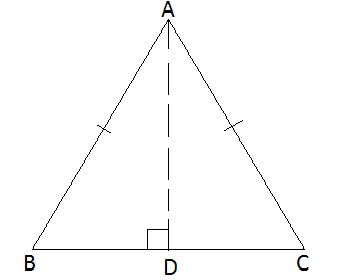

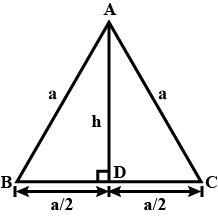

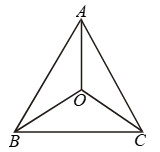

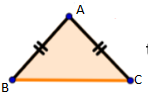

In figure, PQ ≠ QR ≠ PR, so ΔPQR is a scalene triangle. In figure, AB = AC, so ΔABC is an isosceles triangle.

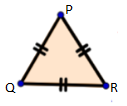

In figure, AB = AC, so ΔABC is an isosceles triangle. In figure, PQ = QR = PR, so ΔPQR is an equilateral triangle.

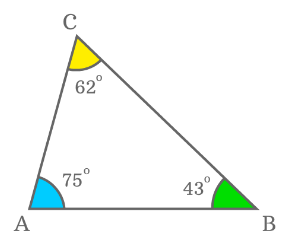

In figure, PQ = QR = PR, so ΔPQR is an equilateral triangle. In figure, ∠A, ∠B, and ∠C are all less than 90°, hence ΔABC is an acute-angled triangle.

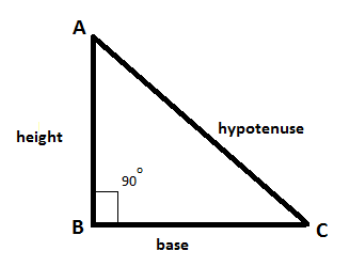

In figure, ∠A, ∠B, and ∠C are all less than 90°, hence ΔABC is an acute-angled triangle. In figure, ∠B = 90°, hence ΔABC is a right triangle.

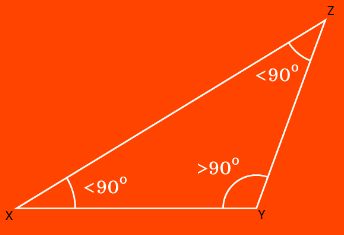

In figure, ∠B = 90°, hence ΔABC is a right triangle. In figure, ∠Y is obtuse, hence ΔXYZ is an obtuse-angled triangle or simply obtuse triangle.

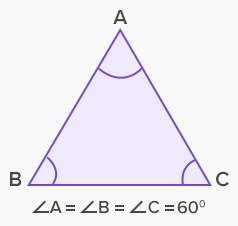

In figure, ∠Y is obtuse, hence ΔXYZ is an obtuse-angled triangle or simply obtuse triangle. In figure, ∠A = ∠B = ∠C = 60°and AB = BC = AC, hence ΔABC is an equiangular triangle.

In figure, ∠A = ∠B = ∠C = 60°and AB = BC = AC, hence ΔABC is an equiangular triangle.